The United States’ booming fossil-fuel industry continues to emit more and more planet-warming methane into the atmosphere, new research showed, despite a U.S.-led effort to encourage other countries to cut emissions globally.

Methane is among the most potent greenhouse gases, and “one of the worst performers in our study is the U.S., even though it was an instigator of the Global Methane Pledge,” said Antoine Halff, the co-founder of Kayrros, the environmental data company issuing the report. “Those are red flags.”

Much of the world’s efforts to combat climate change focus on reducing carbon dioxide emissions, which result largely from the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, and whose heat-trapping particles can linger in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. But methane’s effects on the climate — which have earned it the moniker “super pollutant” — have become better appreciated recently, with the advent of more advanced leak-detection technology, including satellites.

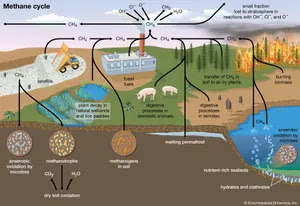

Unlike carbon dioxide, methane emissions don’t derive from consumption, but rather from production and transportation of the gas, which is the main component of what is commonly known as natural gas. Methane can leak from storage facilities, pipelines and tankers, and is also often deliberately released. Methane is also released from livestock and landfills, and occurs naturally in wetlands.

Kayrros focused on fossil fuel facilities, where the practices of “venting,” or the intentional release of large quantities of methane, and “flaring,” which is when it is intentionally burned off, are both common. Kayrros used satellite data combined with artificial intelligence analysis of the data to draw its conclusions.

The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is now more than two-and-a-half times as much as preindustrial levels, and more than half of the world’s methane emissions are man-made.

Its presence in the atmosphere dissipates in roughly 12 years, a relatively short span of time, but numerous studies point to its heat-trapping effects as being as much as 80 or more times stronger than carbon dioxide’s. That means it can have more immediate consequences for the climate.

In 2021, the United States was among the first signers and promoters of the Global Methane Pledge, which set a target of reducing global, man-made methane emissions by 30 percent from 2020 levels within a decade. The pledge has been signed by 158 countries.

“2030 is rapidly approaching, though, and emissions are still being released in huge amounts,” said Mr. Halff. “This seems in large part because oil and gas production is surging both in the U.S. and elsewhere.”

President Biden’s signature climate legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, includes billions of dollars in funding for methane emission-reduction strategies.

According to to the Environmental Protection Agency, the rule could result in the elimination of “more than the annual emissions from 28 million gasoline cars” and “a nearly 80 percent reduction below the future methane emissions expected without the rule.”

The American fossil fuel sector today emits less methane per unit of energy than in years past. However, production has ramped up so significantly that methane emissions overall have increased. The United States is now, by far, the world’s leading gas producer and exporter.

China is the world’s largest emitter of both carbon dioxide and methane, and has not signed the pledge. John Podesta, the U.S. climate envoy, recently traveled to Beijing to meet with China’s top climate negotiators and the two countries agreed to co-host a summit on methane coinciding with this year’s main climate summit in Azerbaijan in November, raising hopes that China might sign this year.

The Kayrros report includes findings from 13 fossil fuel basins across the world, including in three countries that haven’t signed the pledge: Algeria, Iran and South Africa. In those three countries, methane emissions rose even more steeply than in signatory countries.

“It shows the pledge has influence,” said Jutta Paulus, a member of the European Union Parliament from the German Green party who was recently the bloc’s rapporteur on greenhouse gas emissions. She also noted that “many of the fixes are within reach. Leak detection and repair, management of abandoned facilities, they aren’t impossible. In fact, many of them can be done at almost no cost.”

The European Union introduced a regulation this summer that drafts all its member states into a process of studying their own methane emissions and setting targets for reducing them. Perhaps more significantly, starting in 2029, it will apply the same stringent caps on emissions to its imports, including of gas from countries that haven’t signed the pledge, like Algeria. In 2030, the E.U. would begin imposing fines on imports above a certain emissions threshold.

Australia and Turkmenistan were the only two countries in the study that saw major reductions in methane emissions. Australia’s success was likely related to policies aimed at limiting the intentional release of gas during coal production, Mr. Halff said. Turkmenistan, which in many cases operates leaky, decades-old Soviet gas infrastructure, has begun a process of updating its facilities.

No comments:

Post a Comment