Photo: Bloomberg

Attempts in Kolkata and across

India to improve resilience to extreme heat have often been equally

ill-conceived, despite a death toll estimated at more than 24,000 since

1992

By Rajesh Kumar Singh

In scorching heat on a busy Kolkata street last month, commuters sought

refuge inside a glass-walled bus shelter where two air conditioners

churned around stifling air. Those inside were visibly sweating, dabbing

at their foreheads in sauna-like temperatures that were scarcely cooler

than out in the open.

Local authorities initially had plans to install as many as 300 of the

cooled cabins under efforts to improve protections from a heat season

that typically runs from April until the monsoon hits the subcontinent

in June. There are currently only a handful in operation, and some have

been stripped of their AC units, leaving any users sweltering.

“It doesn’t work,” Firhad Hakim, mayor of the city of 15 million in

India’s eastern state of West Bengal, said on a searing afternoon when

temperatures topped 40C. “You feel suffocated.”

Attempts in Kolkata and across India to improve resilience to extreme

heat have often been equally ill-conceived, despite a death toll

estimated at more than 24,000 since 1992. Inconsistent or incomplete

planning, a lack of funding, and the failure to make timely preparations

to shield a population of 1.4 billion are leaving communities

vulnerable as periods of extreme temperatures become more frequent,

longer in duration and affect a wider sweep of the country.

Kolkata, with its hot, humid climate and proximity to the Bay of

Bengal, is particularly vulnerable to temperature and rainfall extremes,

and ranked by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as among

the global locations that are most at risk.

An increase in average global temperatures of 2C could mean the city

would experience the equivalent of its record 2015 heat waves every

year, according to the IPCC. High humidity can compound the impacts, as

it limits the human body’s ability to regulate its temperature.

Even so, the city — one of India's largest urban centers — still lacks a formal strategy to handle heat waves.

2015 - 2024

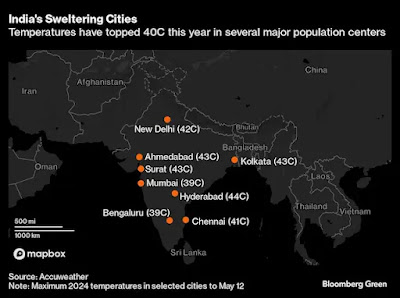

Several regions across India will see as many as 11 heat wave days this

month compared to 3 in a typical year, while maximum temperatures in

recent weeks have already touched 47.2C in the nation’s east, according

to the India Meteorological Department. Those extremes come amid a

national election during which high temperatures are being cited as

among factors for lower voter turnout.

At SSKM Hospital, one of Kolkata’s busiest, a waiting area teemed last

month with people sheltering under colorful umbrellas and thronging a

coin-operated water dispenser to refill empty bottles. A weary line

snaked back from a government-run kiosk selling a subsidised lunch of

rice, lentils, boiled potato and eggs served on foil plates.

“High temperatures can cause heat stroke, skin rashes, cramps and

dehydration,” said Niladri Sarkar, professor of medicine at the

hospital. “Some of these can turn fatal if not attended to on time,

especially for people that have pre-existing conditions.” Extreme heat

has an outsized impact on poorer residents, who are often malnourished,

lack access to clean drinking water and have jobs that require outdoor

work, he said.

Elsewhere in the city, tea sellers sweltered by simmering coal-fired

ovens, construction workers toiled under a blistering midday sun, and

voters attending rallies for the ongoing national elections draped

handkerchiefs across their faces in an effort to stay cool. Kolkata’s

state government in April advised some schools to shutter for an early

summer vacation to avoid the heat.

Since 2013, states, districts and cities are estimated to have drafted

more than 100 heat action plans, intended to improve their ability to

mitigate the effects of extreme temperatures. Prime Minister Narendra

Modi’s government set out guidelines eight years ago to accelerate

adoption of the policies, and a January meeting of the National Disaster

Management Authority pledged to do more to strengthen preparedness.

The absence of such planning in Kolkata has also meant a failure to

intervene in trends that have made the city more susceptible.

Almost a third of the city’s green cover was lost during the decade

through 2021, according to an Indian government survey. Other cities

including Mumbai and Bangalore have experienced similar issues. That’s

combined with a decline in local water bodies and a construction boom to

deliver an urban heat island effect, according to Saira Shah Halim, a

parliamentary candidate in the Kolkata Dakshin electoral district in the

city’s south. “What we’re seeing today is a result of this

destruction,” she said.

Hakim, the city’s mayor, disputes the idea that Kolkata’s preparations

have lagged, arguing recent extreme weather has confounded local

authorities. “Such a kind of heat wave is new to us, we’re not used to

it,” he said. “We’re locked with elections right now. Once the elections

are over, we’ll sit with experts to work on a heat action plan.”

Local authorities are currently ensuring adequate water supplies, and

have put paramedics on stand-by to handle heat-induced illnesses, Hakim

said.

Focusing on crisis management, rather than on better preparedness, is

at the root of the country’s failings, according to Nairwita

Bandyopadhyay, a Kolkata-based climatologist and geographer. “Sadly the

approach is to wait and watch until the hazard turns into a disaster,”

she said.

Even cities and states that already have heat action plans have

struggled to make progress in implementing recommendations, the New

Delhi-based think tank Centre for Policy Research said in a report last

year reviewing 37 of the documents.

Most policies don’t adequately reflect local conditions, they often

lack detail on how action should be funded and typically don’t set out a

source of legal authority, according to the report.

As many as 9 people have already died as a result of heat extremes this

year, according to the meteorological department, though the figure is

likely to significantly underestimate the actual total. That follows

about 110 fatalities during severe heat waves during April and June last

year, the World Meteorological Organization said last month.

Even so, the handling of extreme heat has failed to become a “political

lightning rod that can stir governments into action,” said Aditya

Valiathan Pillai, among authors of the CPR study and now a fellow at New

Delhi-based Sustainable Futures Collaborative.

Modi's government has often moved to contain criticism of its policies,

and there is also the question of unreliable data. “When deaths occur,

one is not sure whether it was directly caused by heat, or whether heat

exacerbated an existing condition,” Pillai said.

In 2022, health ministry data showed 33 people died as a result of heat

waves, while the National Crime Records Bureau – another agency that

tracks mortality statistics – reported 730 fatalities from heat stroke.

Those discrepancies raise questions about a claim by India’s government

that its policies helped cut heat-related deaths from 2,040 in 2015 to 4

in 2020, after national bureaucrats took on more responsibility for

disaster risk management.

Local officials in Kolkata are now examining potential solutions and

considering the addition of more trees, vertical gardens on building

walls and the use of porous concrete, all of which can help combat urban

heat.

India’s election is also an opportunity to raise issues around poor

preparations, according to Halim, a candidate for the Communist Party of

India (Marxist), whose supporters carry bright red flags at campaign

events scheduled for the early morning and after sundown to escape

extreme temperatures.

“I’m mentioning it,” she said. “It’s become a very, very challenging campaign. The heat is just insufferable.”

No comments:

Post a Comment